I wasn’t sure how I was going to feel about the Barbie movie. As a young girl, I didn’t see myself reflected in the Barbie world and my family couldn’t afford the Dream Houses and Cars and Campers I circled in the JCPenney catalogue.

Still, I loved Barbie. I had two Barbies, a Ken, and a bed made out of a showbox and a tissue paper, and that was all I really needed for the first romance stories I made up, where a naked, amnesiac Ken showed up in a middle of a storm, “good” Barbie placed him in her bed to recover, and her bad evil twin Barbie (you could tell she was evil because of her cut hair and marker makeup) seduced him. I didn’t know what seduction involved. I just knew it was the basis of many of the TV shows we watched.

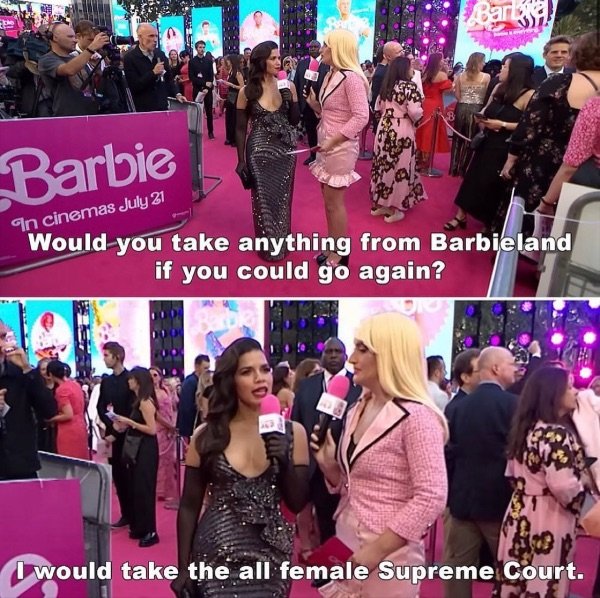

Seeing the spirit of how young girls interacted with Barbie on the big screen was a delight. But even more thrilling, from a personal standpoint, was watching Latina move star America Ferrera talk about the impossible standards set for today’s women.

America Ferrera is the physical model for Gillian Armstead-Bancroft, my once-perfect but now struggling wife, mom, financial planner, and bruja from Full Moon Over Freedom, and that she was the one outlining how woman are made to feel that they are never enough was an absolute triumph.

You have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can’t ask for money because that’s crass. You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead, but you can’t squash other people’s ideas. You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman, but also always be looking out for other people. You have to answer for men’s bad behavior, which is insane, but if you point that out, you’re accused of complaining. You’re supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you’re supposed to be a part of the sisterhood. But always stand out and always be grateful. But never forget that the system is rigged….I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. (You can read the full monologue here.)

My entire writing career has been about creating heroines who show up on the page not caring about being “liked,” who worry more about achieving something meaningful to themselves than appeasing the whims of others. They have a journey, they have things they need to figure out, but fundamentally believing in their worthiness is not one of them.

These heroines have repeatedly been called “unlikeable.” Predominantly by women.

So while I enjoyed the movie and leaned into the fantasy of Barbie defeating the patriarchy, more enjoyable for me was watching a Latina heroine outlining the way it is and calling it bullshit.